The Fall of 2008 marked the

beginning of a long continual slide in the value of the U.S. Dollar vs. hard

assets as the Fed initiated various forms of direct (and indirect) debt

monetization and emergency loans – much of it directed at major financial

institutions (both U.S. and foreign). And U.S. taxpayers have been

picking up the ‘inflation’ bill (primarily food and energy) ever since.

“The Quiet Coup,” by Simon Johnson, The Atlantic May 2009 – Excerpts:

In its depth and suddenness, the

U.S. economic and financial crisis is shockingly reminiscent of moments we have

recently seen in emerging markets (and only in emerging markets): South Korea

(1997), Malaysia (1998), Russia and Argentina (time and again). In each of

those cases, global investors, afraid that the country or its financial sector

wouldn’t be able to pay off mountainous debt, suddenly stopped lending. And in

each case, that fear became self-fulfilling, as banks that couldn’t roll over

their debt did, in fact, become unable to pay. This is precisely what drove

Lehman Brothers into bankruptcy on September 15 [2008], causing all sources

of funding to the U.S. financial sector to dry up overnight. Just as in

emerging-market crises, the weakness in the banking system has quickly

rippled out into the rest of the economy, causing a severe economic contraction

and hardship for millions of people.

But there’s a deeper and more

disturbing similarity: elite business interests—financiers, in the case of the

U.S.—played a central role in creating the crisis, making ever-larger

gambles, with the implicit backing of the government, until the

inevitable collapse. More alarming, they are now using their influence to

prevent precisely the sorts of reforms that are needed, and fast, to pull the

economy out of its nosedive. The government seems helpless, or unwilling, to

act against them.

Of course, this was mostly an

illusion. Regulators, legislators, and academics almost all assumed that the

managers of these banks knew what they were doing. In retrospect, they didn’t.

AIG’s Financial Products division, for instance, made $2.5 billion in pretax

profits in 2005, largely by selling underpriced insurance on complex, poorly

understood securities. Often described as “picking up nickels in front of a

steamroller,” this strategy is profitable in ordinary years, and catastrophic

in bad ones. As of last fall [2008], AIG had outstanding insurance on more than

$400 billion in securities. To date, the U.S. government, in an effort to

rescue the company, has committed about $180 billion in investments and loans

to cover losses that AIG’s sophisticated risk modeling had said were virtually

impossible.

Stanley O’Neal, the CEO of Merrill

Lynch, pushed his firm heavily into the mortgage-backed-securities market at

its peak in 2005 and 2006; in October 2007, he acknowledged, “The

bottom line is, we—I—got it wrong by being overexposed to subprime, and we

suffered as a result of impaired liquidity in that market. No one is more

disappointed than I am in that result.” O’Neal took home a $14 million bonus

in 2006; in 2007, he walked away from Merrill with a severance package worth

$162 million, although it is presumably worth much less today.

In October [2009], John Thain,

Merrill Lynch’s final CEO, reportedly lobbied his board of directors for a

bonus of $30 million or more, eventually reducing his demand to $10 million in

December; he withdrew the request, under a firestorm of protest, only after it

was leaked to The Wall Street Journal. Merrill Lynch as a whole was

no better: it moved its bonus payments, $4 billion in total, forward to

December, presumably to avoid the possibility that they would be reduced by

Bank of America, which would own Merrill beginning on January 1. Wall

Street paid out $18 billion in year-end bonuses last year [2008] to its New

York City employees, after the government disbursed $243 billion in

emergency assistance to the financial sector.

In a financial panic, the government

must respond with both speed and overwhelming force. The root problem is

uncertainty—in our case, uncertainty about whether the major banks have

sufficient assets to cover their liabilities. Half measures combined with

wishful thinking and a wait-and-see attitude cannot overcome this uncertainty.

And the longer the response takes, the longer the uncertainty will stymie the

flow of credit, sap consumer confidence, and cripple the economy—ultimately

making the problem much harder to solve. Yet the principal characteristics of

the government’s response to the financial crisis have been delay, lack of

transparency, and an unwillingness to upset the financial sector.

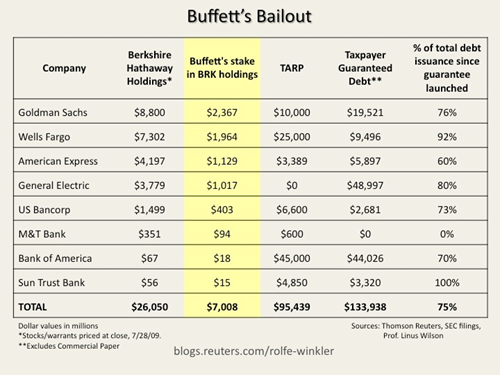

…[TARP] money was used to

recapitalize banks, buying shares in them on terms that were grossly

favorable to the banks themselves. As the crisis has deepened and financial

institutions have needed more help, the government has gotten more and more

creative in figuring out ways to provide banks with subsidies that are too

complex for the general public to understand….

Full article:

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/05/the-quiet-coup/307364/

Simon Johnson, a professor at MIT’s

Sloan School of Management, was the chief economist at the International

Monetary Fund during 2007 and 2008. He blogs about the financial crisis at

baselinescenario.com, along with James Kwak, who also contributed to this

essay.

…………………………………

Note – The Leviticus 25 Plan, featuring direct credit extensions from the Federal Reserve to American families via a ‘Citizens Credit Facility,’ would provide for massive debt reduction and at the family level, and financial rejuvenation for Main Street America.

This ‘ground level’ solution is critical for reducing the scope of Government, slashing government deficits, and re-igniting long-term economic growth.

Any objection that The Leviticus 25 Plan might be unfair to banks ignores the damage that banks did to themselves and to the economy with their greed-slaked thirst for risk and profits during the preceding 10 years.

The time has arrived for American families to receive their own just considerations – direct credit extensions from the Federal Reserve.

The Leviticus 25 Plan – An Economic Acceleration Plan for America

$75,000 per U.S. citizen – Leviticus 25 Plan 2020 (3277 downloads)